The French mission to Ecuador, South America

In May 1735 a scientific expedition left the French port city of La Rochelle to travel to Ecuador, South America. Actually, their final destination wasn’t “Ecuador”, but the Audiencia de Quito. That is, the Province of Quito, at the time still part of the Spanish colony of Peru. (See my earlier post: Ecuador: What’s in a name)

The French expedition was led by three men, three scientists: Louis Godin, Pierre Bouguer & Charles-Marie de la Condamine.

Godin was the formal leader of the expedition, but due to differences in characters, all three had their own responsibilities.

- Note: The Spaniards never liked the idea of other European powers sneaking around in their colonies. It was only because of the Bourbon-connection that the French got permission from the Spanish king to travel to South America. From 1700 a branch of the French Bourbons governed over Spain (and still do!).

In Cartagena, Colombia they were joined by two Spanish colleagues – Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa. These two men were included by the Spanish government not only to assist the scientific mission, but also to keep an eye on the French visitors. Once in Ecuador, the expeditionaries soon met a local scientist that would join them as well, Pedro Vicente Maldonado.

The shape of the Earth

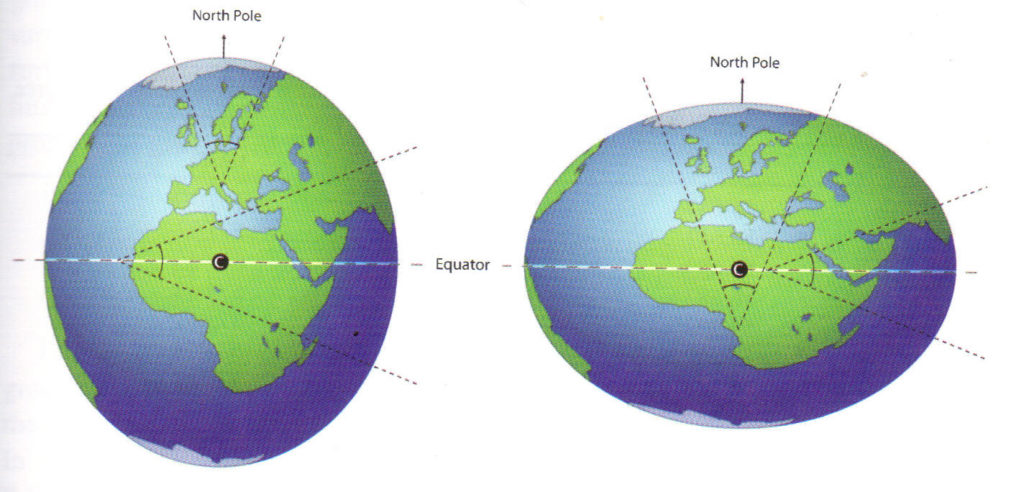

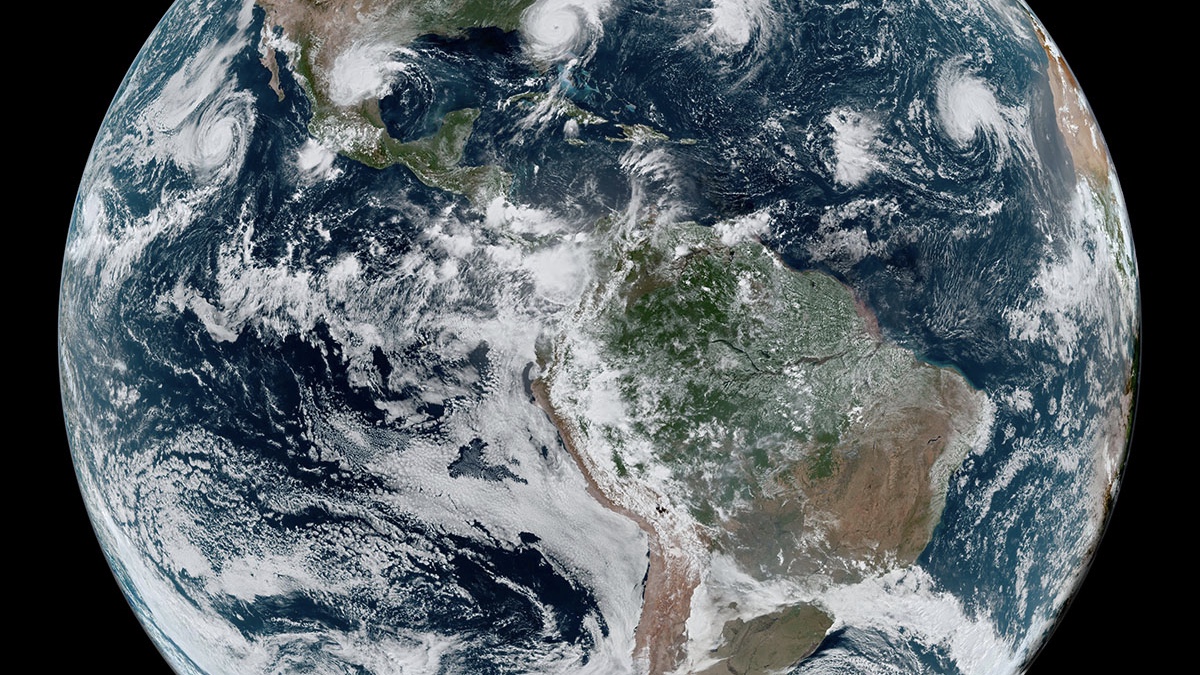

The main reason for the French geodesic mission to travel to South America was a hot-headed discussion in Europe – mainly between scientists in England & France – about the shape of the Earth.

In summary, the French scientists – following the ideas of Descartes and the mapmakers’ family of the Cassinis – were convinced that the Earth was expanding at the poles (like a lemon). While the English experts – lead by Newton’s revolutionary theories published in 1687 – were certain that our planet expands at the Equator (like a mandarin).

After one too many discussions, the French decided to do the test. In other words, to go out and actually measure the Earth. Not only at the Equator, but also at the Poles.

The expedition to Ecuador, South America

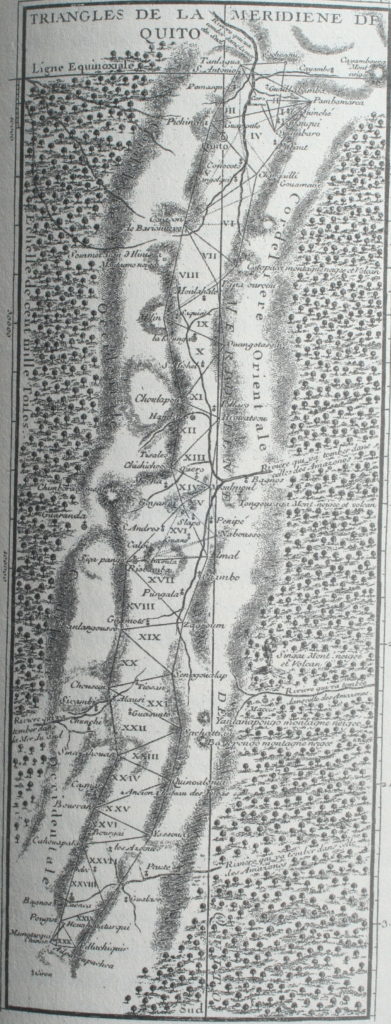

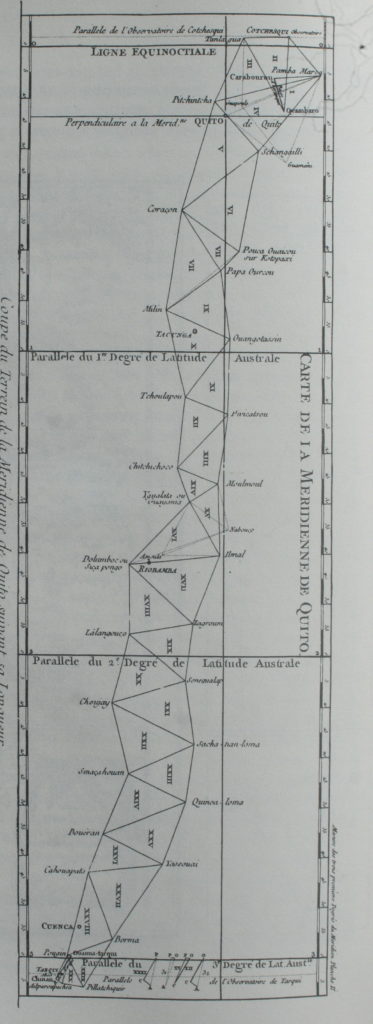

The first mission to travel, was the “South America”-expedition. The concrete goal: to measure the length of a degree of latitude at the Equator. In practice that would mean measuring the distance from the northern capital Quito to the southern city of Cuenca. In a straight line, a distance of about 300 kilometers/ 188 miles.

Beforehand the expeditionaries thought they could do their job in half a year. In practice though, it would take them almost six years. The main reason for the delay being the difficulty of the terrain. The mighty Andes mountains were their working area.

Method of Triangulation

The method for measuring the Earth” was called Triangulation. A method that starts with a meticulously measured baseline, after which you search for a third spot in the landscape which you can see from both ends of the baseline. In this way forming a triangel.

Through measuring the exact angle from both ends to that third point, it’s possible to calculate the length of the other two sides of the triangel through a formula. After you’ve got the length of all sides, you can continu on with the next (bordering) triangel, until completing the whole distance you planned to measure. Hope you get it! If not, the following illustration may help.

The French expedition started their work near Quito with a baseline (just over 12 kilometers long/ 7.5 miles long). From there, they worked their way to Cuenca in the south. Meanwhile, always on the lookout for the highest points in the landscape, and measuring triangel by triangel.

A demanding job

Because the scientists had chosen the Andes as their working area, they had to climb almost every volcano along the Andean highway. The mountain tops of both cordilleras that run through Ecuador from north to south, like the Cotopaxi, the Ilinizas, the Chimborazo. A hard task, the men being scientist in the first place, not athletes.

- Note: To be honest, the scientist didn’t need to go all the way to the top. They had to climb high enough though, to be able to see the next measuring point (sometimes 40-50 kilometers/ 25-30 miles away). Generally they ended up near the snow line.

- Note: At the time, the French visitors thought that Ecuador housed the highest mountains in the world. Like the Chimborazo (6310m/ 20702ft), Ecuador’s #1. Almost sixty years later the famous German scientist Alexander von Humboldt would try to conquer the Chimborazo. He didn’t reach the summit, but he also was convinced it was the highest mountain on Earth.)

Of course, the Andes demanded more of the expeditionaries then they could offer. Climbing up and down with all their scientific equipment and – when finally installed – waiting for the moment to be able to get a clear view of the next observation point (set up by the other members of the expedition). I live for almost 30 years in Ecuador now – see About me – and can tell you that the mountaintops are seldom cloudless.

Other obstacles on their historic path

Besides the many setbacks on the mountains, too often the scientists had to work with ignorant authorities. They had to deal with the mistrust of most inhabitants – many of whom were convinced that the strange men were looking for gold, silver or some hidden treasure, like the Spaniards had done just a few centuries before.

And then there were the scientific errors & mistakes, the conflicts between the members of the expedition, the sicknesses & deadly diseases, falling in love with the local beauties. Even the death of two expeditionaries had to be endured. One died of a disease soon after arrival. The other one was murdered in Cuenca by a jealous competitor for the hand of a young women.

Six years later …

Finally in 1742 they could end their work and take home the results. Results that in the end proved to be only partially correct, and – besides that – came too late. Their colleagues at the Poles (Sweden-Finland) had done their job much faster and had concluded, without a doubt, that the Earth was expanding at the Equator. In other words, the English were right after all.

- Note: Nowadays we know Mount Chimborazo isn’t the highest mountain in the world. However, because of the expansion on the Equator, standing on the summit of Chimborazo means you’re farthest out from the center of the Earth.

Of course, the men that had chosen to travel to South America were frustrated by the fact that they were beaten. To somehow rescue their scientific mission, several members took advantage of their presence in a unique country in the world. They made studies of the people, their culture, as well as the flora & fauna before sailing home. De la Condamine, after finishing his work in Ecuador, even decided to travel the Amazon-river downstream to Brasil. One of the first scientist to do so.

An amazing story

Besides the scientific aspects, the visit of the French Mission to Ecuador, South America is full of travel adventure, misfortunes, discoveries and several remarkable love stories. In all, such an amazing story that I decided to write it down many years ago. Resulting in De Aarde is niet rond (2014) (Only available in Dutch so far – through clicking on the title or through contacting me).

Coming up: The pyramids

After finishing the measurements, it was Charles-Marie de la Condamine who decided that their work & presence in Ecuador needed a monument. So, he planned to build two pyramids. Each pyramid marking the end of the baseline near Quito, the place were everything started.

In a next post I will tell you about: These pyramids, their construction, what happened to them after the French expedition left and how I finally found them myself. Although forgotten… they still stand proud!

Besides these monuments, there are many others that I will sum up for you in a fourth & final post.

What De la Condamine and the others couldn’t know at the time is, that the biggest “monument” they left the country was its name: Ecuador.

*****

- For all the latest news on Ecuador, join my Visit Ecuador Facebook Group.

.

For an overview of all travel posts of my blog, go to: the Home Page.

.

Comments

One response to “Ecuador: How to measure the Earth”

[…] Ecuador: To measure the Earth […]